Organizations excel when they connect their business, brand, and marketing strategies. Doing so increases internal efficiency and creates a scalable foundation for future growth.

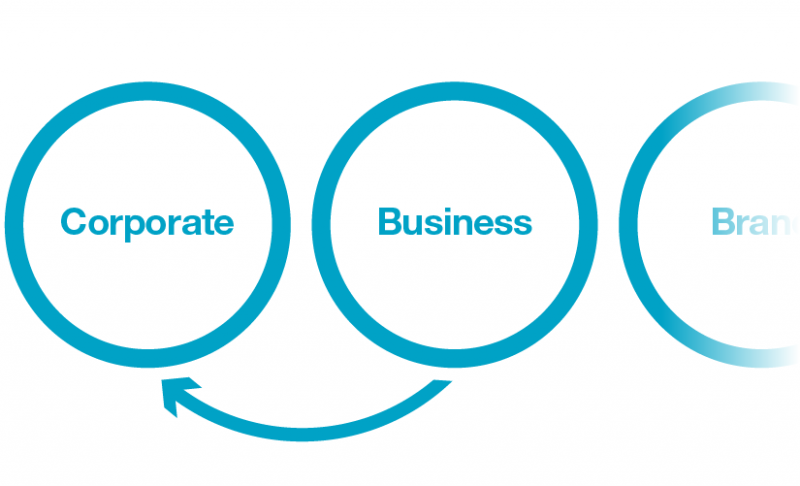

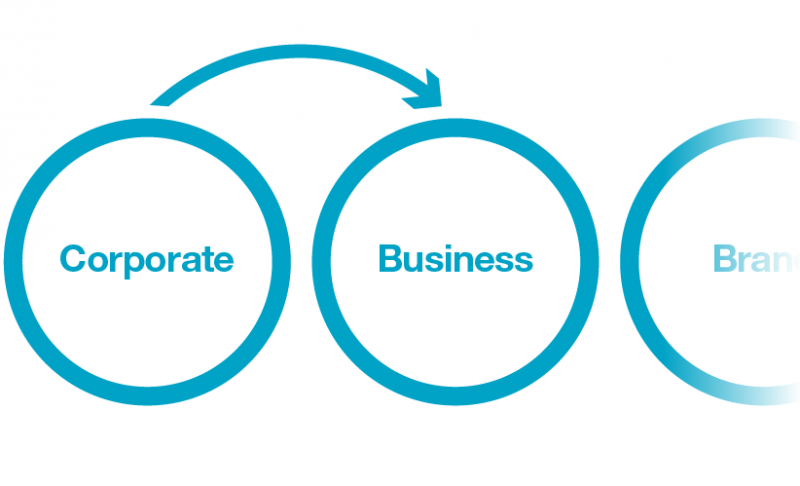

I’ve been fleshing out this idea for several years as a series of concepts and practical exercises, starting with my original post “Three kinds of strategy” (2012), up to the most recent one “Brand marketing vs. performance marketing” (2017). I’ve explored each of these three circles from left to right—from business vision to full-funnel marketing analytics.

But this simple picture I’ve been painting is incomplete. Today, I want to complicate it slightly, by adding a new thought, and, for the first time, a fourth circle: corporate strategy.

What is corporate strategy?

Corporate strategy might at first seem like the same thing as business strategy, but they are different. In 2012 Ken Favaro wrote a helpful article in strategy+business that distinguishes clearly between the two. Business strategy deals with external market opportunity, while corporate strategy deals with organizational structure and operations. According to Favaro, the two essential questions of corporate strategy are: (1) What businesses should we be in? and (2) How organizationally do we add value to those businesses?

In other words, business strategy might get you an iPod, but corporate strategy gets you tight supply chain controls, a long-term plan for minimizing taxes, and an R&D engine that can produce regular hit products over time.

At first, corporate strategy is dependent on business strategy. For example, Apple creates a breakthrough product and then perfects an operational model to do so repeatably for years. Or a startup founder with a bright idea seeks VC investment, and those investor expectations thereafter dictate the speed and priorities of the business. Or a nonprofit sets a BHAG and then fleshes out the operational imperatives to achieve that goal.

Over time, however, corporate strategy tends to become its own machine, leading the organization into either complacency or else new territories, new questions, and new visions for the future.

There’s a wealth of publicly available information about corporate strategy, including many business magazines like s+b that target enterprise executives and management consultants, and startup blogs that discuss COO hiring, financing round do’s-and-don’ts, and board composition. I don’t want to repeat what others have said and said well.

I do want to point out that corporate strategy looks and feels different depending on the size and nature of the organization. At enterprise scale, corporate strategy tends to be a front-and-center, well-understood concern. It structures daily conversations, investments, and projects. There’s a system-level methodology that GMs, COOs, and CFOs can use to evolve the corporate strategy, working up, down, and across business units. Anand Sanwal, founder of CB Insights, writes about this in his book Optimizing Corporate Portfolio Management. Favaro notes this too:

“For most large, complex companies, the questions of corporate strategy… are relevant at multiple levels, not just for the company overall. For example, a division with multiple businesses (consider consumer banking at Citi or GE’s industrials group) represents more of a corporate portfolio than a single business unit. In fact, most divisions, segments, groups, and even business units can be thought of as having a portfolio of smaller businesses within them, thus making the questions of both corporate and business strategy relevant to their strategies.”

Below enterprise scale, the questions that Favaro associates with corporate strategy are still important, but I find they often get insufficient attention. The phrase “corporate strategy” for obvious reasons can seem abstract or irrelevant to SMBs, nonprofits, and young startups. At these smaller levels of scale, the line between business and corporate strategy can blur, and as a result, core questions about operational models and organizational design might never get asked. Or they might get asked once and then never again.

One way to ensure that questions about business strategy and business models are being asked and answered appropriately is to focus on who is asking the questions. This usually involves scrutinizing the beliefs, behaviors, composition, and activities of the board. At any organization larger than a sole proprietorship, the board determines, instantiates, limits, or is a highly involved participant in setting the corporate strategy.

If we want to unlock human energy in pursuit of our defined opportunity—if we want to find the organizational and operational model that best facilitates, supports, and extends our business strategy—we have to think about the board.

Who really matters

Art Kleiner has written what to me is the most useful book for understanding board dynamics. His book Who Really Matters: The Core Group Theory of Power, Privilege, and Success punctures the illusion that corporations are customer-centric:

“‘The customer comes first’ is one of the three great lies of the modern corporation. The other two are: ‘We make decisions on behalf of our shareholders’ and ‘Employees are our most important asset.’ Government agencies have their own equivalent lies: ‘We are here to serve the public interest.’ Nonprofits, associations, and labor unions have theirs: ‘Above all else, we represent the needs of our members.’” (Kleiner, Who Really Matters)

Who really does come first is what Kleiner calls the Core Group, which can vary by organization and is often hiding in plain sight. The Core Group warps priorities, thinking, and behavior. Ultimately, it will make its presence known and felt on the board, via who makes decisions and, more importantly, “all the people whom decision makers keep in mind.” These phantom influencers might include the CEO, funders, founders, family members, emeritus executives, personal mentors, or a default culture that’s implicitly biased against anyone with a different background or point of view.

At a few points in his book, Kleiner recommends visualizing how fiefdoms and individuals on the board can form alliances with each other, or with departments and individuals on the staff, or with external stakeholders, leading to a set of inter-locking cliques that makes efficient progress against the vision impossible.

I’ve seen many flavors of board dysfunction, and some prevalent ones are worth listing. (I may do so in a later article.) When I think of board optimization, however, I’m usually not thinking of horror stories, but of the everyday, unavoidable ways that all human groups get bogged down. I agree with Kleiner that there’s always a Core Group, invisibly pulling the organization away from what it says and ostensibly intends.

This, as it turns out, is a feature of human nature, not a bug. In his wonderful and occasionally heady book The Ecology of Attention, Yves Citton writes that “we never have the means to pay enough attention” and so we end up paying attention to what preoccupies others. Limited attention leads to groupthink: we pay attention to what others in the group pay attention to, reacting to and in the context of other people’s priorities, in an endless feedback loop. Attention, in other words, is “an essentially collective phenomenon: ‘I’ am only attentive to what we pay attention to collectively.”

In a similar, if geekier, vein Citton writes:

“The intra-cerebral attention nanoeconomy, modelled in terms of zones, synapses, nerve impulses and neurotransmitters, only makes any sense if it is re-situated within the microeconomy of small groups in which we develop on a daily basis (family, office, business) and the macroeconomy of great media flows which take up and captivate our consciousness.”

We are always in groups: the human species is inherently and intensely social. But in groups, we can neither see straight nor think straight: group reality starts to supplant and obscure other realities. We may or may not be consciously aware of this, but either way, the intra-organizational conflicts that lead to gridlock and inefficiency, once established, tend to be undiscussable and their undiscussability is undiscussable.

The Core Group often functions within an organization like an addiction. Its goal is to hijack attention and prevent other realities from coming into view. This dynamic will be all-too-familiar to anyone who has grown up in an alcoholic household where gaslighting, codependence, and denial are the norm.

Often, boards and executive teams will bring in a consultant to surface or root out these dysfunctions. This is a good idea: objectivity, baseline intelligence, and what Venkat Rao calls “a missing or dismantled sacredness module” can be very useful to shine a light and expand what the organization can pay attention to.

Granted, being a consultant who exposes the undiscussable is a tricky role. Each current team member wants to keep her or his job, prestige, or in-group status. Conscious incompetence brings up strong negative emotions. Outsiders are threatening. Any consultant who comes on too strong runs the risk of being demonized, like the Witch in Into the Woods who sings “I’m not good, I’m not nice, I’m just right” before leaving the tribe in despair. You can be right, or you can be in a relationship, as they say.

Thinking outside-in

When I work with boards, my objective as a consultant is usually to get the team working on the task of aligning corporate and business strategy, rather than serving the interests of the Core Group. This work can involve ego confrontation, humility, and tough conversations, and sometimes but not always, it takes time.

One helpful fact is that when I work with an organization, it by definition already exists. Unlike a startup founder, I’m not trying to make something—I’m trying to make something better. So my first step is always evaluation.

One way to evaluate what the corporate strategy should be is to look at it through the lens of the business strategy—in other words, to start with the vision. All human organizations are moving consciously or subconsciously towards their goals. Making those goals concrete, visual, and measurable can unlock appropriate thinking—and new thinking—about how best to achieve them.

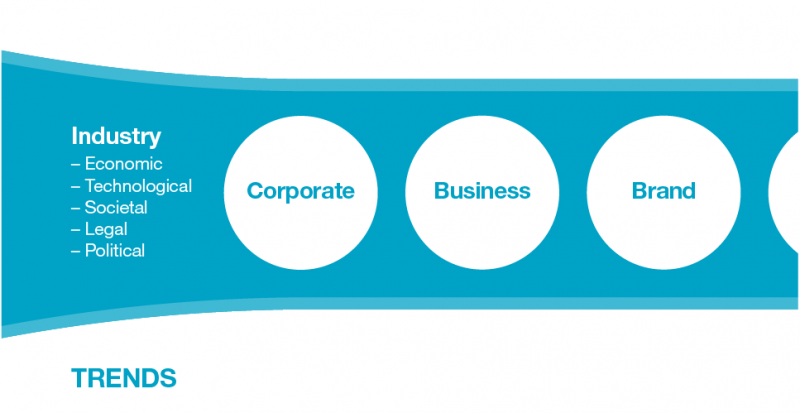

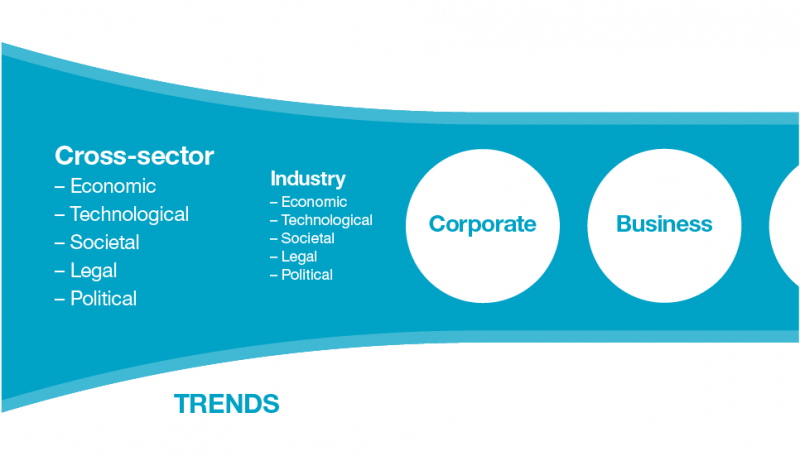

Another approach is to look at the organization from the outside-in. If we wanted to extend our four-circles diagram a bit further, we might show corporate strategy taking place in the context of dynamic external trends:

Some of these trends are industry-specific. Board members and senior staff are often recruited for their expertise within said industries, which can be invaluable. The legal, technical, and operational quirks of healthcare, manufacturing, and fintech (for example) are complicated and not learned overnight. Know-who in most industries trumps know-how, and it can take an entire career to build the right connections.

That said, organizations can easily over-value expertise within their own industry, at the expense of understanding cross-industry and cross-sector trends. A dangerous yet inevitable problem as organizations disrupt themselves and challenge new categories is that the team can get attached to outdated ways of looking at things, not noticing that the corporate strategy needs to evolve. For example:

- We used to be a school, but now we’re in the education business.

- We used to sell hardware, but now we’re in the software business.

- We used to run a TV network, but now we’re in the media business.

- We used to be a bricks-and-mortar retailer, but now we’re an omnichannel retailer.

- Etc.

Successful organizations find that thinking horizontally (across industries and sectors) as well as vertically (within industries) is practically useful, and increasingly so. Benedict Evans noted in passing in one of his recent newsletters that B2B and B2C business models have hybridized in recent years:

“L’Oréal bought Modiface, an AR beauty app. Lots of consumer brands that don’t actually have a consumer relationship (effectively, they’re B2B companies selling only at wholesale) thinking about how they can talk directly to their customers.”

Likewise, the so-called FAGA monopolies of Facebook, Amazon, Google and Apple are all B2B2C businesses, spanning multiple industries, and all are deeply dependent on, and interdependent with, the public sector.

Given all this blurriness, a “big zoom” perspective is often useful. Here are some current mega-trends that, depending on your situation, may directly inform corporate strategy:

- Global economic fragility

- Broken/saturated media ecologies

- Climate change

- First- and second- order effects of new technologies

- Social inequality

- Geopolitical tension

- Data and application security

- Org models that combine gig economy, gift economy and salaried employment in new ways

All topics for future posts.

# # #

Note: The ordering of corporate and business strategy in my diagram is debatable because as I’ve noted, it’s contextual: at different phases of growth, one kind of strategy might lead the other, and then switch. I err towards putting it at the front of the queue because it illustrates how corporate strategy can either influence or constrain vision—literally what we pay attention to. Also, asking the question “what kind of business should we be in?” often precedes identifying our unique opportunity within that competitive space. If my abstraction is admittedly crude or a bit flawed, it nevertheless can provoke effective and important conversations, which ultimately, with all frameworks and metaphors, is as good as it gets.

Leave a Reply