I.

In the mid-nineteenth century, German composer Richard Wagner, inspired by the ancient Greeks, began advocating for a synthesis of all art forms—drama, music, dance, poetry, spectacle—into what he called a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art. His vision came closest to realization in his 17-hour Ring Cycle and in his Bayreuth opera house, which he had custom-built to stage his epic works.

The design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus is innovative and meticulous. Famously, the giant orchestra is nested underneath the stage, which allows the singing actors to project over Wagner’s dense scores without barking or straining their voices. Orfeo International recently released a live 1958 recording of Birgit Nilsson singing Isolde at Bayreuth, and the balance between the singer and the orchestra is indeed exceptional.

For opera-lovers, the yearly pilgrimage to Bayreuth was and remains a tradition with obvious religious overtones. Gesamtkunstwerk as a concept borrows heavily from religious ceremonies that for centuries have united environment and art to captivate, integrate, and transform communities.

Wagner has had an enduring influence on Western culture since his death, not only in the world of music and aesthetics. Erich Ludendorff, the losing German general of World War I, used a reference from the Ring to claim brazenly and falsely that the homefront Germans, allied with Jews and degenerates, had “stabbed them in the back” and thus ensured the German defeat. This myth would later be promulgated by the rising Nazi Party, and Hitler’s personal love of Wagner would give the composer a central place in Nazi culture.

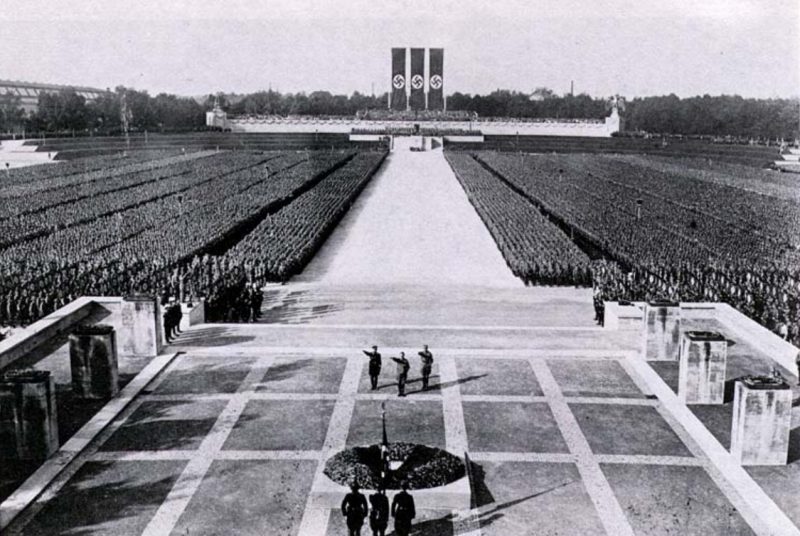

Though Hitler’s direct reports generally did not share his love for Wagner, Wagner’s music nevertheless was heavily featured at the annual Nuremberg Party Rallies. Pilgrims to Nuremberg were greeted with a new kind of Gesamtkunstwerk, carefully crafted by Hitler and the Nazi leaders, that included theatricality and strict control of space, consistent and prominent logos, and artful use of film and modern amplification to induce religious fervor and passive acceptance of Nazi control.

II.

Perhaps it’s just me, but whenever I think of Gesamtkunstwerk, I also think of enantiodromia…

Enantiodromia is a Greek term used by Carl Jung to describe a tendency for movements and forces to turn into their energetic (shadow) opposite. An example of enantiodromia is when the black sheep of a family is judged and rejected for spurious reasons, but then, once rejected, she becomes the hard-hearted monster the family imagines her to be.

Enantiodromia is central to many Greek tragedies, where heroes like Oedipus try strenuously to avoid some fate, but in doing so, they bring that fate about. The wonderful documentary Protagonist explores how this tendency is implicit in human life. Children turn into their parents, inclusive groups become exclusive groups, revolutions replicate the problems of the systems they originally overthrew, freedom fighters become terrorists.

I think that enantiodromia is key to understanding the aftermath of WWII, what happened next, and what happened after that.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Western intellectuals and artists like Theodor Adorno, Margaret Mead, and John Cage were terrified by the totalitarian movements that led to the war. In mass culture—and particularly in popular music—some of them saw the emergence of dangerous and similar patterns, where young people were happy and willing to surrender their agency completely to a “parent” influence. These intellectuals and artists worked actively, often with federal government support, to foster “democratic” experiences—in museums, happenings, and public spaces—that would connect individuals with their own subjective points of view, and that would break up totalitarian media control.

They won and they lost. As Fred Turner points out, the fruits of their efforts paid off exactly where these intellectuals wouldn’t expect nor want it: in the Human Be-In of 1967 and the Summer of Love that followed—i.e., at a rock concert. Turner writes: “The children of the 1960s did not only overthrow their parents’ expectations. They also fulfilled them.”

The hippie generation, passionate about individuality, social progress, drug culture, and the liberating potential of networked technology, would put down roots and pick up jobs in the defense-funded companies of Silicon Valley, spurring the next wave of economic progress and technology development that we live with today. A love movement finding a home (and an income) within a war machine.

An obvious poster child for this transition is the wunderkind Apple founder and CEO Steve Jobs. Jobs’ product launches for Apple remain superlative examples of showmanship, brand-building, and tribe-building. They were not just announcements, but genuine events, with every aspect of logo placement, spectacle, music, and sound design carefully crafted to induce agreement, to induce awe.

This should look familiar at this point.

III.

The story of Gesamtkuntswerk continues from the iPhone launch to our present day. But it also stretches back in time. It pre-dates Wagner. It even predates cities.

Anthropologist Monica L. Smith has recounted how human hunter-gatherer tribes built religious sites like Stonehenge, and around these sites, they created festivals, where strangeness and strangers, warmth and spectacle, community and commerce would all combine. Later on, cities would represent the possibility of keeping that festival experience going year-round. As Zadie Smith recently described, a city is a kind of living Gesamtkuntswerk, and one’s life there likewise becomes a work of art, energetically omnivorous, borrowed and built from everything around it.

In rural communities to this day, people go to the fair to experience the beyond, the sublime, the different. In cities, they go to the opera house.

IV.

All humans have a yearning to transcend. But the difficult reality is that contemporary life is not a Matrix but instead a Gesamtkuntswerk.

There is no human reality outside Gesamtkunstwerk: all of us are consuming fictions, creating fictions, heading to the festival, shaking our heads in bewilderment that someone else could believe “fake news,” buying the latest device, watching our latest fictions on said device.

David Rock has pointed out that when the brain can’t decide if something is good or bad, it labels it as “very bad.” And so all of us are engaging in casual or runaway splitting, sculpting our perceptions and recollections to make them beautiful, total, true, and trustworthy… if false.

We keep telling the tale again, refining it as we go, hoping to get it right. With every retelling, the story gets more inclusive, more refined, more artful.

But at the same time, we’re trapped by the limits to what any one person can see, our essential drives, and how humans relate to symbols and each other. Sometimes we see a straight line (e.g., from the church to the opera house to the military rally to the product launch to the filter bubble), sometimes a recursion. Sometimes a strange loop, sometimes an eternal return. Sometimes an evolution, sometimes a revolution.

In 2020, the SF Opera will present one of the most celebrated operas of the early 21st century, the (R)evolution of Steve Jobs. I already have my tickets.

V.

My professional craft is “unlocking human energy,” which today happens in the context of leadership, strategy, marketing, and brand consulting. I am often helping organizations tell better stories, create more beautiful and captivating experiences, focus on some things but not other things, succeed even when the game is rigged.

Even for the most well-intentioned organizations, the nature of this work is morally treacherous. A “total work of art” as a phrase suggests both the apogee of human symbolic expression and a complete falsehood. I have many colleagues who will admit without any cognitive dissonance that they choose to believe things they know to be false just to survive.

Here’s what helps me navigate an insane world skillfully for myself and for the organizations I work with:

- I accept that every organization is going to feel the pull to create a message and an “experience” that’s beautifully self-consistent, if detached from the realities of their product, their culture, and the outside world.

- I accept as a given that human beings are limited, and our perceptions, wants, and survival needs are going to twist us to re-organize the world to suit our human priorities. We are human, and humanity is both wonderful and terrible. Humanity, for better or worse, is what we have to work with.

- I accept that our deepest sense of fulfillment can come when we are caught up in a lie, whether that lie is the Ring, an origin myth, a new Apple device, or a beautiful story about who is right and who is wrong or what is good and what is not.

- I appreciate how Gesamtkunstwerk thrives on nuance—the yearning of the violins, the graceful curve of an iPhone, the just-right Instagram filter, the throw pillow placed just-so—adding more sparkle and vitality to our felt existence. And at the same time, it obliterates nuance, obscuring anything outside its own incomplete totality, its lie.

- I accept that ambivalence, though uncomfortable, can be adaptive.

- Like the Met Opera conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin, I cultivate a cold mind and a warm heart.

VI.

Classical music critic and cultural historian Alex Ross recently said of Wagner:

“[T]o equate him with Hitler ignores the complexity of his achievement and in the end does little more than grant Hitler a posthumous victory. The necessary ambivalence of Wagnerism today can play a constructive role: It can teach us to be generally more honest about the role that art plays in the world.

In Wagner’s vicinity, we cannot claim to fantasies of the pure, autonomous work of art. We cannot forget how art unfolds in time and unravels in history. And so Wagner is liberated from the mystification of great art. He becomes something more unstable, perishable, and mutable. Incomplete in himself, he requires the most active and critical kind of listening…

I think this disturbing kind of intervention of reality and history might make for almost a deeper experience, certainly a more complex one. And so we shift from a kind of adoration and immersion to an experience that has this critical dimension to it. So we are always aware, we are always a little wary of Wagner. We should be.”

Be artistic. Be critical. Be aware. Be wary.